Scott Kerlin, M.S., Ph.D., with Ian Cameron BSC {Hons} MA, Bob Klaehn, M.D., DFAACAP, and Laura Henton, DNP, APRN, FNP-C

DES International Research Network

February 2026–Comprehensive Update–Academic Literature Review

I. Introduction: Since beginning my academic graduate studies more than 40 years ago, I have been engaged in researching the complexities of gender identity, as an outgrowth of my own interdisciplinary graduate education and my childhood experiences living with gender dysphoria and gender curiosity. Over the years I have learned that the scope of published research in this entire area is quite substantial.

Purpose of this Report

This research digest is a comprehensive bibliography of published scientific literature focusing on the multiple issues relating to gender identity in individuals, including clinical research, comprehensive assessment, biological and neurological components, medical and psychotherapeutic treatment, and other healthcare interventions. It is an extension of my historical investigation of biological factors influencing psychosexual and gender identity development in humans, a field to which I have been deeply focused since the 1990s.

About Dr. Kerlin and the Goal of My Research

I am a confirmed DES son, meaning that I have medically verified that I was exposed prenatally to the endocrine-disrupting drug diethylstilbestrol. I was born in the early 1950s, and I was medically treated for intersex condition at birth and in early childhood; I have also been treated for hypogonadism since my early 20s. Knowledge of this information led me in the 1990s, following completion of my PhD in 1992, to begin investigating the role of DES and similar endocrine-disrupting chemicals in shaping human sexuality and gender identity in humans. In 2005, I authored and presented my first major report, “Prenatal Exposure to Diethylstilbestrol (DES)in Males and Gender-Related Disorders: 5-Year Study.”

Having accepted many years ago that I had strong cross-gender feelings when I was a child, I have come to identify as gender-nonbinary. The journey of self-discovery and self-acceptance has not always been easy, but my depth of research investigation has aided my own compassion for others who have been asking questions similar to my own.

In the mid-1990s, I launched a private professional practice providing confidential supportive professional counseling and mental health services for individuals who identify as transgender, non-binary, LGBTQI+ and questioning with regard to their gender and sexual identity.

Over the years, I have interviewed and surveyed and surveying hundreds of individuals focusing their understanding on their own sexuality and gender identity. Through my interviews I learned that a significant proportion identified on the LGBTQ-Non-binary spectrum. My research was first documented by Deborah Rudacille, M.A., in her 2005 book The Riddle of Gender, and supported by the late Dr. Milton Diamond, Ph.D., Professor of Anatomy and Reproductive Biology at the John A. Burns School of Medicine at the University of Hawaii, Dr. Aaron Devor, Ph.D.,, (the inaugural Chair in Transgender Studies at the University of Victoria, and the founder and subject matter expert of the Transgender Archives, and most recently Dr. Charles Sultan, Professor of Endocrinology at M.D., Ph.D., Chief of the Pediatric Endocrine Unit at the University Hospital of Montpellier, France.

For me, the most essential understanding that represents my ongoing scientific investigation of gender identity is that there are major biological factors that underpin the development of gender identity in humans, as well as psychological factors.

Most recently, my research on gender identity is cited in two investigative publications, one of which (2024) I am co-author:

>> Gaspari, L., Soyer-Gobillard, M.-O., Kerlin, S., Paris, F., & Sultan, C. (2024). Early Female Transgender Identity after Prenatal Exposure to Diethylstilbestrol: Report from a French National Diethylstilbestrol (DES) Cohort. Journal of Xenobiotics, 14(1), 166-175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox14010010

>> Soyer-Gobillard, M.-O., Gaspari, L. & Sultan, C. (2025), Gender identity disorders: a legacy of fetal exposition to Diethylstilbesterol, an Endocrine Disruptor Chemical. The European Society of Medicine Medical Research

Archives, online 13(3). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i3.6342 .

I strongly recommend this reference book: Wolf-Gould, C., Denny, D., Green, J. & Lynch K, eds., (2025) A History of Transgender Medicine in the United States: From Margins to Mainstream (Albany: State University of New York Press).

Our Co-Researchers:

(Our Consultant) Bob Klaehn, M.D.

I am a confirmed “DES son.” I was exposed to Diethylstilbesterol in utero during mid-fifties. My mother, a Registered Nurse, told me of my DES exposure after my first urology appointment at age 20. However, it took another 40+ years to fully include this information in my life’s narrative. After my second genitourinary cancer (Bladder Cancer in 2010 and Prostate Cancer in 2020), I began to research the subject in detail and began to re-interpret my life story based on the feminizing effect that DES has had on my neurons. Based on this research and ongoing therapy, I came out as genderqueer within the last few years.

Professionally, I am a Board-Certified Adult and Child Psychiatrist and a Distinguished Fellow of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP). I retired from a career in clinical and administrative psychiatry, with a focus on the diagnosis, treatment and management of Autism Spectrum Disorder. I was Medical Director for the Arizona Division of Developmental Disabilities (DDD) for nearly fourteen years, providing medical management for the Medicaid Carve-out Health Plan for DDD-enrolled individuals. I also had the opportunity to provide “house calls” to develop comprehensive treatment for individuals with Autism or Intellectual Disability plus complex mental health issues across the state.

I am an active local, national and international speaker on topics in early childhood mental health and the diagnosis and treatment of persons with Autism Spectrum Disorder and other Developmental Disabilities. In December 2019, I presented four lectures during the international conference “At the Juncture of Psychiatry and Neurology: Disorders in Infants, Adolescents and Young Adults,” in Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine. I have continued to provide Continuing Medical Education to Ukrainian Psychiatrists throughout the pandemic and Russian invasion via the Internet.

I received my undergraduate degree in History and Science from The Johns Hopkins University in 1976 and my medical degree from Wayne State University in Detroit in 1980. I received my adult and child psychiatry training at the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics. I am currently Clinical Assistant Professor of Psychiatry for the Creighton University School of Medicine – Phoenix.

About Ian Cameron BSC {Hons} MA

I am a DES son on the basis my mother told me. I have a range of autoimmune conditions, ASD, and an intersex condition, XXY Klinefelter, confirmed by a consultant. On that basis I have an interest in research into Diethylstilboestrol and intersex/gender topics. I was born in 1956 in London, England and often wondered why I felt I didn’t fit in, or belong anywhere, and that something was wrong with me , but not knowing what.

I have spent most of my working life in local government involved in landscape management, conservation and planning at a senior level. I started my working life in Horticulture and Botany.

I have a Bachelors degree in Biology and a Masters degree in Environmental Science, gained through study with the UK Open University.

About Dr. Henton

I am a confirmed DES daughter, meaning that I have medically verified that I was exposed in utero to the endocrine-disrupting drug diethylstilbestrol (DES). I was born in the late 1950’s in western Massachusetts, where my mother was treated in a high-dose cohort. I have received medical and surgical treatment for my DES-related gynecological structural and cellular abnormalities.

I have been working as a nurse since the early 1980’s in a wide variety of settings. I’ve obtained a BSN (Kent State University) & MSN (Walden University); more recently earned the Doctorate of Nursing Practice (DNP) in the Family Nurse Practitioner (FNP) track. I am now pursuing a post-doctorate Psychiatric/Mental Health Nurse Practitioner (PMHNP) certificate from Shepherd University.

II. Areas of Our Overarching Research Focus

How To Use This Report

[December Note: This section is under development, so far with 26 specific research questions and relevant published literature listed below. For each question, the literature that we have identified to have strongest relevance is identified by (Notable).]

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Gender Identity and Transgender Research

Chapter 2: Gender Dysphoria

Chapter 3: Gender Incongruence

Chapter 4: Nonbinary Identities and Prevalence

Chapter 5: Measures of Gender Identity

Chapter 6: Gender Identity Research with Youths

Chapter 7: Support for People Exploring their Gender Identity

Chapter 8: Mental Health Assessment, Issues and Gender Identity

Chapter 9: Mental Health Treatments and Outcomes for Gender Dysphoria

Chapter 10: Gender-affirming Healthcare

Chapter 11: Additional Healthcare Topics for Transgender and Nonbinary Populations

Chapter 12: Older Adults & Gender Identity–Major Issues

Chapter 13: Resilience in People with Diverse Gender Identity

Chapter 14: Concealment, Stigma, and Disclosure of Gender Identity

Chapter 15: Suicide risk among gender-diverse individuals

Chapter 16: Gender Euphoria in Gender-diverse Individuals

Chapter 17: Gender Fluidity in Adults and Youths/Children

Chapter 18: Body image and medical surgery/transition for Gender-diverse Individuals

Chapter 19: Sexuality Among Transgender and Gender-diverse Individuals

Chapter 20: Sexual Function and Transgender Individuals

Chapter 21: Endocrine Disruptors: Links to Sexuality and Gender Variations in Humans

Chapter 22: Broadening Research on Transgender Identity, Health, and Support

Chapter 23: Disorders/Differences of Sexual Development (DSD) and Related Topics

Chapter 24: Studies of Personal Narratives on Self-discovery about Gender Identity

Chapter 25: Association Between Autism and Variations in Gender Identity

Chapter 26: What are the biochemical pathways that result in the Transgender Brain?

Here is a list of our principal major research questions for Chapters 1-26, each with a summary overview along with relevant studies that have assisted our summative inquiry.

Principal research questions:

>> (Chapter 1) How has gender identity and transgender identity been scientifically researched and investigated over the past few years, and what are the leading issues that continue to be explored in the published literature?

by Ian Cameron and Scott Kerlin

Overview: The process of gender identity development is a highly complex and dynamic experience for each individual. Researchers have covered a broad range of issues associated with identity formation, sometimes distinguishing “gender identity” from “transgender identity”.

Oda and Stiehl [2025] note that in the U.S., approximately 13 million individuals identify as part of a sexual and gender minority (SGM). This broad spectrum includes sexual orientation identities such as gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer, pansexual, and same-gender-loving, as well as gender identities such as transgender, gender non-conforming, bigender, and two-spirit. As behaviour analysts heed the call to engage in culturally competent practices that address diverse sexual orientation and gender identities (SOGI), they will likely consider collecting SOGI data as part of their practice. The benefits of SOGI data collection certainly exist. However, the historical oppression and increased vulnerability of SGM populations require a careful and thorough evaluation of ethical data collection practices to avoid harm and to ensure respectful and inclusive practices.

Given that the dominant discourse about these topics is still grounded in binary measures (Rushton et al., 2019), professionals may overlook the complexity of these constructs and the ongoing cultural competence necessary to address these topics effectively (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2022). With soundly designed procedures and a clear rationale, SOGI data collection can both validate respondents’ identities and yield rich information related to these core identities. Conversely, poorly designed SOGI data procedures risk harming sexual and gender minority (SGM) respondents and can result in the collection of misrepresentation or data that may not accurately reflect the diversity of SOGIs.

Many behaviour-analytic domains may benefit from SOGI data collection, such as clinical practice, Organizational Behaviour Management (OBM), research, education, supervision, and public health. An obvious benefit is learning about respondents’ experiences and needs to better support them. Behaviour analysts must understand that SGM populations constitute a historically oppressed group that is particularly vulnerable to harm.

Self-report is the only socially valid method for SOGI data collection. Research studies and interventions are usually tied to ethical standards, guidelines, and legal policies related to confidentiality. Question framing can influence whether respondents understand the question, feel safe to answer honestly, and experience feelings of affirmation or harm when participating. Using open-ended questions or statements allow for the most descriptive and unbiased SOGI data collection.

From: What do measures of gender identity tell us about gender identity over time? Fisher, Wright and Sargeant [2024] British Journal of Developmental Psychology.

Gender identity is a multifaceted concept and is represented by a wide range of measures and constructs including both self-report and researcher observations of preferences and behaviours. However, despite their similar theoretical underpinning, gender identity measures are rarely found to correlate with one another, and contrasting patterns and trajectories are often found for each construct

The results of this review are consistent with wider research suggesting that distinct developmental patterns can be observed when using different constructs and measures of gender identity. Gender-diverse individuals have been present throughout history and experiences outside of the gender binary are found in cultures around the world.

There are a range of underlying assumptions about what ‘gender’ means and this can vary based on cultural and societal norms. Morgenroth and Ryan (2018) argue that conceptual understandings of gender fall into 3 categories: (1) evolutionary understandings based on biological sex, (2) social structural approaches based on societal norms and structures, and (3) social identity approaches based on gender as a social category with which an individual identifies. Across the research literature, ‘sex’ is often used to refer to the biological characteristics of an individual (e.g., chromosomes), while ‘gender’ typically refers to the societal and cultural meanings associated with femininity and masculinity (Lindqvist et al., 2021). The term ‘transgender’ is operationalized by Lindqvist et al. as ‘individuals whose assigned gender at birth does not correspond to their self-defined gender identity’. These ‘assigned genders’, given to infants at birth, are often based on a dichotomous binary categorization of gender and sex. Some cultures hold on to the belief that gender is a binary system and there are distinct differences between men and women. This can lead to discrimination, self-stereotyping, stereotype threat and institutional biases (Hyde et al., 2019).

With rising numbers of individuals whose experience cannot be defined using these binary categories, theories of gender identity have broadened, reflecting ideas of gender as a spectrum (Gülgöz et al., 2022) with multiple co-occurring constructs (Ho & Mussap, 2019). These perspectives date back to earlier works by Butler (1990) and West and Zimmerman (1987), who argued that ‘gender’ is a performance that we ‘do’ repeatedly based on societal stereotypes, reinforcing an illusion of binary sex. Viewing gender as a societal construct rather than a characteristic determined by biological sex has led to an affirmative model of care being used internationally with gender-diverse individuals, supporting an individual to consolidate their expressed gender (APA, 2015). These models are based on research suggesting that societal expectations and pressure to conform to gender norms have a negative impact on psychological outcomes. A greater awareness of how an individual’s gender identity develops over time, as evidenced by a combination of measures, may support a more nuanced understanding of gender identity development.

Another key finding of this systematic review is that when children reach middle childhood their self-identified gender tends to remain consistent over time (Hässler et al., 2022)

From: Sex/gender diversity and behavioral neuroendocrinology in the 21st century. Costo and Money [2024] Hormones and Behaviour

What does our science really say about sex and gender diversity? And further, what are the unintended consequences of research that involves sex/gender, particularly with regards to the lives of marginalized populations? Even if the science were settled on these matters (and we argue that it is not), to what extent is it appropriate to use research findings to decide who qualifies for protection against discrimination?

Most scientists who study topics like sexual differentiation or sexually selected traits arrive at the lab each day and divide their samples into two categories: female and male. This earnest and logical adherence to the dictum of precedent and the presumed laws of nature feels to many as an ordinary and self-evident ritual. The result is a methodology that relies on a binary before the study even begins.

One main purpose of sexual reproduction is thought to be to facilitate genetic diversity, and the phenotypes related to sexual reproduction itself are among the most plastic and diverse. The genes and other molecular mechanisms that drive sex-related differentiation and behavior are themselves extraordinarily unstable and vary strikingly across taxa, even among closely related species (Capel, 2017). Thus, evoking the existence of gametes and their obvious distinctions as a counterargument to sex/gender diversity is ineffective and distracts from the broader complexity. Moving away from traditional paradigms and toward those that help us understand diversity is a critical task whose time has come.

One well-intentioned approach to allow for broader conceptualizations of sex diversity has been to draw a sharp distinction between “biological sex” (a term with a long history of being used to deny rights; Clarke, 2022) and “gender.” This practice is problematic for two reasons. First, sex and gender are not easily separable in the context of biomedical studies (Pape, 2021)

Second, using either category as a “variable” interferes with precision because both concepts are constructs—amalgams of a variety of traits and other factors (Massa et al., 2023). A second approach to gender inclusivity within biomedicine has been advocacy for and implementation of policies mandating inclusion of females and males in biomedicine research. A false binary.

Studies that are inclusive to trans and gender-diverse (TGD) people are essential to the scientific record yet are notably rare. In addressing this issue, it is critical that studies are designed with a sensitivity to intervening factors affecting marginalized groups

In the words of Roughgarden (2004), “The biggest error of biology today is uncritically assuming that the gamete size binary implies a corresponding binary in body type, behavior, and life history.”

Dividing a sample into two crude categories, male and female, ignores and flattens this complexity, much of which depends on factors such as social context, environmental conditions, developmental time points, and model organisms. Region-by-region analysis of male and female-typical measures of single brains showed a mosaic pattern – within any one individual, areas usually considered to be sex-differentiated on the aggregate may look sex-conforming, nonconforming, or undifferentiated.

As more and more scientists comply with new sex-inclusive policies, the need for forward-thinking tools and training becomes more urgent. At this time in history, research affecting marginalized genders must be rigorous, reproducible, and gender-informed (Massa et al., 2023; McLaughlin et al., 2023; Pape, 2021; Pape et al., 2024; Richardson, 2022; Rich-Edwards et al., 2018). Roughgarden (2004) wrote: “Although biological differences can be found between the sexes and between people of differing gender expression and sexuality, biological differences can also be found between any two people. Behavioural neuroendocrinology has been at the forefront of discovery on the hormonal, genetic, and neural processes underlying sexual differentiation and sex differences in behaviour.

From: How Transgender Adolescents Experience Expressing Their Gender Identity Around New People: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Wilson, Malik and Thompson. [2021] Journal of Adolescent Research Sage Journals.

Transgender young people are individuals whose gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. In recent years, the number of adolescents seeking support with gender dysphoria (distress resulting from the incongruence between assigned and experienced gender) has significantly grown (Gender Identity Development Service [GIDS], 2021a). Gender expression to be a key experience of transgender young people that may impact upon the development of their gender identity and psychological well-being.

The establishment of identity is thought to be the primary developmental task of adolescence, during which young people explore different identities through social interactions and eventually form a more stable sense of self (Erikson, 1968). Exploring and expressing one’s gender in social relationships is, therefore, a key part of the development of our internal sense of gender identity. Research with transgender adults indicates that these ideas also apply to the development of transgender identity.

Gender expression and related social experiences have both positive and negative impacts upon the psychological well-being of transgender individuals. Kozee et al. (2012) propose that expressing oneself in a way that is congruent with one’s gender identity while feeling authentic and genuine is important to well-being, and in a study with transgender adults found greater gender congruency to be associated with reduced anxiety and depression, and greater life satisfaction. Gender expression is also important in providing opportunities for affirmation, or social recognition and support, of one’s gender identity. Sevelius’ (2013) gender affirmation framework proposes that social affirmation of gender is important in confirming transgender individuals’ sense of self, and further studies have found affirmation to be related to increased psychological well-being and self-confidence, and reduced dysphoria (Rood et al., 2016; Russell et al., 2018; Sevelius et al., 2021). However, by disclosing and expressing their gender identity, transgender youth also risk being disaffirmed or misgendered, and exposed to gender-based social oppression, stigma, and victimization.

Participants described feeling a need to conform to socially constructed expectations of masculinity to be recognized as male, both in their outward appearance and behaviour and more internally, such as the way they managed and expressed emotions. Most participants found being gendered correctly, or affirmed, to feel significant and positive in the moment, and to have a lasting effect on their emotional well-being and confidence. The feeling of exhausting hyperawareness shared by participants when initially expressing their gender, that became more natural over time. As found in studies of transgender identity development, rather than solely being a means to communicate gender and develop a social identity as male, gender expression also appeared to enable participants to explore, develop, and strengthen their internal sense of their gender identity. The findings also demonstrate that it is important transgender young people are supported to manage stress associated with expressing their gender identity around others.

Research is also warranted in exploring the causal links between experiences of affirmation and misgendering on well-being, and the influence of participant characteristics, such as demographics, access to support, and resilience/coping strategies, on the impact of these experiences.

From: More Than Social Stigma Meets the Eye: The Inherent Struggle of Sexual and Gender Identity Development Across the Lifespan, Bockting [2024] American Journal of Psychiatry.

The findings from this study are consistent with previous research that showed poorer mental health and well-being among plurisexual women. For example, in a longitudinal study of sexual minority women, bisexual and “mostly heterosexual” women were most likely to report hazardous drinking and depression. These findings are typically attributed to the lack of available group-level coping for plurisexual individuals (i.e., a community of gay and lesbian people is more developed and more readily available than a community of bisexual people).

In addition to social and environmental factors so well explicated in the minority stress model, there may be other reasons why changes in sexual or gender identity across the lifespan may be associated with psychological distress, poorer mental health, and decreased well-being. First and most generally, for many people, change is stressful. Among trans and nonbinary people, struggling with one’s gender identity was found to be associated with mental health concerns independent of social stigma. Second, without stress, there might be no growth.

A broader array of theoretical frameworks should be explored to guide the study of sexual and gender minority health and to elucidate developmental vulnerabilities and resiliencies across the lifespan of individuals in relation to their socioecological environment. Finally, we need to use the knowledge already gained to inform and test psychotherapeutic as well as social interventions to mitigate inequities and promote LGBTQ+ people’s health and well-being.

The genetics and hormonal basis of human gender identity. Batista and Loch. [2024] Archives of Endocrinology and Metabolism

Gender identity refers to one’s psychological sense of their own gender. Establishing gender identity is a complex phenomenon, and the diversity of gender expression challenges simplistic or unified explanations. For this reason, the extent to which it is determined by nature (biological) or nurture (social) is still debatable. The biological basis of gender identity cannot be modeled in animals and is best studied in people who identify with a gender that is different from the sex of their genitals such as transgender people and people with disorders/differences of sex development. Numerous research studies have delved into unraveling the intricate interplay of hormonal, neuroanatomic/neurofunctional, and genetic factors in the complex development of core gender identity. In this review, we explore and consolidate existing research that provides insights into the biological foundations of gender identity, enhancing our understanding of this intriguing human psychological trait.

Sexual differentiation involves the development of distinctions between males and females, a phenomenon observed widely in nature, including in human biology. A notable sexually dimorphic trait in humans is gender identity, defined as an individual’s intrinsic perception of themselves as female, male, or as a gender alternative to conventional male and female classifications. In cisgender individuals, the gender identity aligns with the gender assigned at birth and remains consistent throughout their lifespans. Conversely, transgender individuals may consistently or intermittently identify with a gender different from the one assigned at birth.

Given the intricate nature of this framework and its clinical implications, significant attention has been dedicated to understanding the origins of the sexual differentiation process. it is firmly established that biology plays a pivotal role. Accumulating evidence suggests that prenatal sex hormones exert a lasting impact on human sexual development, and heritability studies suggest the involvement of genetic components.

Human sexual development is a dynamic process regulated by genes and executed by endocrine mediators in the form of steroids and peptide hormones. The first stage of sexual development is determined by chromosomal sex (presence of the X or Y chromosome). This chromosome will influence the determination of gonadal sex, differentiating the bipotential gonad into ovaries or testes. The presence and expression of the SRY gene (located on the distal portion of the short arm of the Y chromosome) direct gonadal differentiation toward testes, forming Leydig and Sertoli cells. Sertoli cells produce anti-Müllerian hormone, which causes the involution of Müllerian derivatives, while Leydig cells produce testosterone, differentiating Wolffian ducts into vas deferens, epididymis, and seminal vesicles. The conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone by the action of 5α-reductase type 2 occurs between the sixth and twelfth weeks of gestation and is essential for the development of male internal genital organs and the virilization of external genitalia.

Sexual development continues after gonadal differentiation with cerebral sexual differentiation, occurring in the second half of gestation, where gonadal steroids (especially testosterone) act, even in the prenatal period, causing organizational effects on the brain, leading to permanent changes in brain structure and sexual behaviour. Cerebral sexual development follows the same dynamics as gonadal development, where the presence of androgens is necessary for male development. Gender identity can arise from a complex interplay between nature (biology) and nurture (social).

The authors identified a unique link between TA repeats in ERα and gender dysphoria. Utilizing a binary logistic regression model, the study concluded that certain allele and genotype combinations of ERβ, ERα, and AR are implicated in the genetic basis of transgender identity. Specifically, male-to-female gender development requires AR, accompanied by ERβ, with an inverse allele interaction observed between ERβ and AR in the male-to-female population. Additionally, ERβ and ERα are associated with male gender identity in the female-to-male population, although no interaction between the polymorphisms was found. These findings underscore the significant role of ERβ in human brain differentiation.

Epigenetics explores how external factors influence gene expression and phenotype without altering the underlying DNA sequence, shedding light on how environmental cues shape biological traits across generations.

In the early stages of development, testosterone plays a crucial role in shaping the mammalian brain’s sexual differentiation, leaving lasting impacts on behaviour. In humans, testosterone levels rise in males from approximately weeks 8 to 24 of gestation and resurface during early postnatal development (mini puberty).

Conditions related to prenatal androgen exposure have been a model for studying the influence of sex steroids on gender behaviour. Differences/disorders of sex development (DSD) is a collective term for a group of relatively rare congenital conditions associated with an alteration in chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomic sex. In brief, 5α-reductase is the crucial enzyme for synthesizing dihydrotestosterone from testosterone. In foetuses lacking 5α-reductase, the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone does not occur during the critical period of external genitalia differentiation. Since dihydrotestosterone is essential for external genital virilization, their genitalia appear typically female or only mildly masculinized at birth. However, individuals with 5α-reductase type 2 deficiency still produce and respond to testosterone in a manner similar to unaffected males. They undergo virilization during puberty if their testes remain in place, subject to the effects of prenatal testosterone exposure.

Many sex differences in human brains are evident in the sizes of particular brain regions. The caudate nucleus, hippocampus, Broca’s area, anterior commissure, and right parietal lobe are larger in females than in males, while the hypothalamus, stria terminalis, and amygdala are larger in males than in females. Most sex differences in the brain have been investigated in regions important for sexual function and reproduction, such as the hypothalamus. The influence of gonadal hormones on the sexual differentiation of these structures has been studied extensively, for instance, in the case of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area. There is evidence that sex differences in cortical structure vary in a complex and highly dynamic way across the human lifespan.

Eliot and cols. believe that the human brain is not “sexually dimorphic” because differences between male and female brains are extremely subtle and variable. The term “dimorphism” has potent heuristic value, reinforcing the belief in categorically distinct organs: a “male brain” and a “female brain” that have been evolutionarily shaped to produce two psychologically distinct categories of people. A picture is emerging not of two brain types nor a continuous gradient from masculine to feminine, but of a multidimensional “mosaic” of countless brain attributes that differ in unique patterns across all individuals.

In conclusion, the exploration of gender identity reveals a multifaceted interplay between biological and social factors, highlighting the complexity of its development. Genetic studies have identified potential links between specific genes and transgender identity, shedding light on the genetic underpinnings of gender identity. Neuroanatomic and neurofunctional differences between sexes have been observed, suggesting possible neurobiological correlates of gender identity. Studies on transgender individuals’ brains have revealed structural shifts toward their gender identity, supporting the neurobiological basis of gender identity. Overall, the intricate nature of gender identity is influenced by several biological factors. However, the orchestration of gender identity encompasses multiple rhythms, lacking exclusivity or singularity. Instead, it manifests as a diverse and plural human phenomenon.

Doyle (2022) observes, “Identity sits at the core of transgender experience. Transgender people are those whose gender identity (and/or expression) does not match their gender assigned at birth, including non-binary and gender diverse individuals. For transgender people, internally recognizing and externally expressing an authentic gender identity can be a complex and shifting process, requiring careful navigation of potentially supportive or hostile social circumstances.”

Wilson, et al. (2021) recognize that the psychological nature of gender identity formation is a combination of individual (inner) and social (external/outer) factors.

Research on the biological factors associated with gender identity (for example, genetic, hormonal, physiological, neuroanatomy) continues to evolve, and can at times lead to conflicting or even controversial conclusions. Levin, et al., (2022) conclude “We question the utility of etiological studies in clinical care, given that transgender identity is not pathological. When etiological studies are undertaken, we recommend new, inclusive designs for a rigorous and compassionate approach to scientific practice in the service of transgender communities and the providers who serve them.”

Brumbaugh-Johnson & Hull, 2019 note that transgender individuals, in the “coming-out” process, “make strategic decisions regarding the enactment of gender and gender identity disclosure based on specific social contexts. Coming out as transgender is best conceptualized as an ongoing, socially embedded, skilled management of one’s gender identity.”

Highlighted References (Under development)

Key Literature References

(Notable) *** Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (SOGI): A Tutorial on Ethical Data Practices (2025), by Fernanda S. Oda, published in Behavior Analysis in Practice

(Notable) {NEW} *** How Many Adults and Youth Identify as Transgender in the United States? (August 2025), from the UCLA Williams Institute School of Law

(Notable) *** Diverse Gender Identity Development: A Qualitative Synthesis and Development of a New Contemporary Framework (2024), by Molly Speechley, et al., published in the journal Sex Roles

(Notable) *** What do measures of gender identity tell us about gender identity over time? (2024) by Ellena Fisher, et al., published in the British Journal of Developmental Psychology

*** Beyond Wokeness: Why We Should All Be Using a More “Sensitive” Measure of Self-Reported Gender Identity (2024), by Melissa Marcotte, et al., published in the journal Psychological Reports

*** Neurobiological characteristics associated with gender identity: Findings from neuroimaging studies in the Amsterdam cohort of children and adolescents experiencing gender incongruence (2024), by Julie Bakker, published in the journal Hormones & Behavior

(Notable) *** Sex/gender diversity and behavioral neuroendocrinology in the 21st century (2024), by Kathleen V. Casto & Donna L. Maney, published in the journal Hormones & Behavior

(Notable) *** How Transgender Adolescents Experience Expressing Their Gender Identity Around New People: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (2024), by Hannah Wilson, et al., published in the Journal of Adolescent Research

*** White American transgender adults’ retrospective reports on the social and contextual aspects of their gender identity development (2024), by Emily Herry, et al., published in British Journal of Developmental Psychology

*** Exploring gender diverse young adults’ gender identity development in online LGBTQIA + communities (2024), by Kieran (Kie) Cronesberry, et al., published in International Journal of Transgender Health

*** Gender identity importance in cisgender and gender diverse adolescents in the US and Canada (2024), by Natalie M. Wittlin, et al., published in the British Journal of Developmental Psychology

(Notable) *** More Than Social Stigma Meets the Eye: The Inherent Struggle of Sexual and Gender Identity Development Across the Lifespan (2024), by Walter O. Bockting, Ph.D., published in the American Journal of Psychiatry

(Notable) *** The Genetics and Hormonal Basis of Human Gender Identity (2024), by Rafael Loch Batista, et al., published in Archives of Endocrinology & Metabolism

*** Testosterone, Gender Identity and Gender-stereotyped Personality Attributes (2024), by Kathleen V. Casto, et al., published in Hormones & Behavior

(Notable) *** Transgender and Gender Diverse Identity Development in Pediatric Populations (2023), by Samantha Addante, published in Pediatric Annuals

*** Supporting Transgender/Gender Diverse Identity Development Through Embodied Exploration of Gender Euphoria, Joy, and Resilience, by Ray Ciancoitto (2023), unpublished Masters degree thesis, Sarah Lawrence College

*** Biological Studies of Transgender Identity (2023), by Rachel N. Levin, et al., published in the Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health

(Notable) *** Coming Into Identity: How Gender Minorities Experience Identity Formation (2023), by Sonny Nordmarken, published in the journal Gender & Society

(Notable) *** Sexual orientation in transgender adults in the United States (2023), by Sari L. Reisner, et al., published in BMC Public Health

*** What does Transgender Mean to You? Transgender Definitions and Attitudes toward Trans People (2023), by V. N. Anderson, published in Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity

*** “Trans Enough”: Examining the Boundaries of Transgender-Identity Membership (2023), by David Kyle Sutherland, published in the journal Social Problems

(Notable) *** Transgender identity: Development, management and affirmation (2022), by David Matthew Doyle, published in the journal Current Opinion in Psychology

*** Broadening gender self-categorization development to include transgender identities (2022), by Emma F. Jackson, published in Social Development

*** Gender Identity Development in Children and Young People: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies (2021), by Hannah Stynes, et al., published in the journal Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry

*** Sex, Gender and Gender Identity: A Re-Evaluation of the Evidence (2021), by Lucy Griffin, et. al, published in the journal BJPsych Bulletin

*** The Neuroanatomy of Transgender Identity: Mega-Analytic Findings From the ENIGMA Transgender Persons Working Group (2021), by Sven C. Mueller, et al., published in The Journal of Sexual Medicine

(Notable) *** Navigating identity: Experiences of binary and non-binary transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) adults (2020), by Chassity Fiani, et al., published in The International Journal of Transgender Health

*** Chapter 8 – Biological basis of gender identity (2020), by Alessandra Daphne Fisher & Carlotta Cocchetti, published in The Plasticity of Sex: The Molecular Biology and Clinical Features of Genomic Sex, Gender Identity and Sexual Behavior (ed: Marianne J. Legato)

*** Coming Out as Transgender: Navigating the Social Implications of a Transgender Identity (2019), by Stacey M. Brumbaugh-Johnson, published in the Journal of Homosexuality

*** Transnormativity and Transgender Identity Development: A Master Narrative Approach (2019), by Nova J. Bradford & Moin Syed, published in Sex Roles

(Notable) *** Hormones, Sexual Orientation & Gender Identity (2019), by NC Neibergall, et al., published in The Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology and Behavioral Endocrinology (2019), Chapter 12

*** Gender identity development among transgender and gender nonconforming emerging adults: An intersectional approach (2018), by L. E. Kuper, et al., published in International Journal of Transgenderism

(Notable) *** Neurobiology of gender identity and sexual orientation (2018), by C. E. Roselli, published in Journal of Neuroendocrinology

(Notable) *** Evidence Supporting the Biologic Nature of Gender Identity (2015), by Aruna Saraswat, et al., published in Endocrine Practice

*** Gender Identity Development: A Biopsychosocial Perspective (2014), by Annelou L. C. de Vries , published in Gender Dysphoria and Disorders of Sex Development: Progress in Care and Knowledge

*** (Historical) Witnessing and Mirroring: A Fourteen Stage Model of Transsexual Identity Formation (2004), by Aaron Devor, published in Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy

>> (Chapter 2) How has the concept of gender dysphoria and related research evolved over time?

Overview, by Ian Cameron

Over the past 30 years, the concept of gender dysphoria and major research focusing on it has substantially evolved.

From: What is the Best Approach to Removing the Social Stigma from the Diagnosis of Gender Dysphoria? Milionis, C. [2025]. Health Care Analysis in Springer Nature.

Historically, the transgender population has faced prejudice and discrimination within society. The purpose of diagnostic terms is to direct clinical care and facilitate insurance coverage. However, the existence of a medical diagnosis for gender nonconformity can exacerbate the stigmatization of transgender people with adverse consequences on their emotional health and social life. Whether transgenderism and gender dysphoria are indeed a psychopathological condition or even any kind of nosological entity is a contested issue. Many advocates of human rights, trans activists, social scientists, and clinicians support either the removal of gender incongruence from the list of mental disorders or at least its transfer to a separate category. Reforming the classification is an intermediate step toward depathologization and permits access to transgender-related care. Nonetheless, it partly preserves the stigma associated with abnormality and puts the availability of psychiatric care at risk. A more radical approach dictates that the classification of diseases serves exclusively medical purposes and must be dissociated from the respect for the legitimacy of one’s autonomy and dignity. In the long term, only a swing in societal values can detach stigma from mental and physical illnesses. Enhancing collective respect for life, human rights, and diversity is the best way to achieve cohesion and well-being among members of society. Health professionals can be pioneers of social change in this field.

From: Mapping the evolution of gender dysphoria research: a comprehensive bibliometric study. Aria, M., D’Aniello, L., Grassia, M.G. [2024] Quality and Quantity in Springer Nature

The definition of gender dysphoria has been the subject of extensive scientific debate in various fields. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-V) characterizes gender dysphoria as a psychological condition due to a discrepancy between perceived and assigned gender. The scientific community has engaged in an extensive debate over the years regarding the classification of gender dysphoria, initially characterizing it as a gender identity disorder and subsequently removing it from the category of mental disorder.

This leads to various levels of discomfort, as individuals may feel uncomfortable with their biological sex, primary and secondary sexual characteristics, and social gender roles. Over the years, the scientific debate to establish a clear definition of gender dysphoria and explore the social and psychological consequences for people who experience dysphoria has been varied and has covered different fields of interest

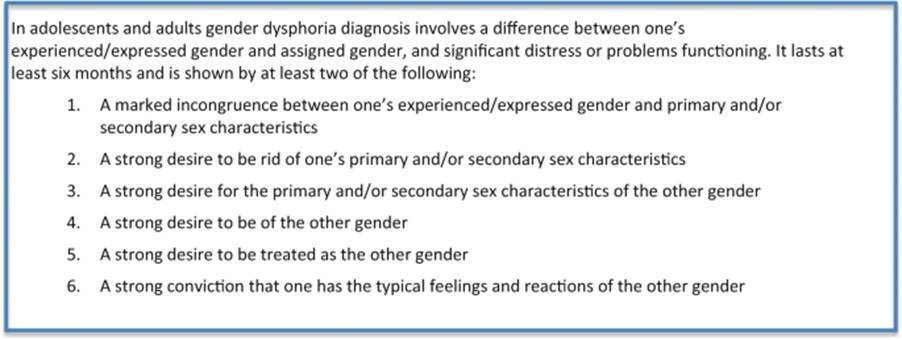

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V), a diagnosis requires a condition persisting for over six months with a presence of at least two of these symptoms:

- Discomfort regarding the alignment of perceived sex and primary and secondary sexual characteristics.

- A desire to change one’s sexual characteristics.

- A wish to acquire the sexual characteristics of the opposite gender.

- An inclination to identify as the opposite gender.

- A longing to be acknowledged and treated as the opposite gender by others.

- A belief in possessing emotions and reactions typical of the opposite gender.

Additionally, the second criterion states that the condition must be associated with clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, affective-relational, and other areas of life. People who experience gender dysphoria may identify themselves as transgender, nonbinary, or, more generally trans , but not all trans and intersex people experience gender dysphoria.

The research delves into the psychological, social, and medical aspects of gender dysphoria, exploring factors like self-acceptance, social support, mental health outcomes, and the effectiveness of different interventions and treatments. Scholars and researchers have engaged in extensive debates regarding gender dysphoria since the 1970 s, leading to a transformative shift in understanding the condition.

Recognizing the evolution of focus and related issues surrounding gender dysphoria is crucial for ongoing progress in the field and providing support to individuals experiencing this condition. Over time, there has been a significant shift in the understanding and approach to addressing gender dysphoria, reflecting an increasing awareness of gender identity. This research played a pivotal role in dispelling myths about sexual orientation, affirming that it is not a choice and is not influenced by psychological or social factors.

These studies highlighted the intricate nature of gender dysphoria, emphasizing its biological basis and establishing the groundwork for evaluating the efficacy of gender-affirming treatments in enhancing the quality of life for individuals with gender dysphoria.

Over the past two decades, shifts in trends and perceptions regarding gender dysphoria have been influenced by a multitude of events such as the LGBTQ + rights movements, the evolution of gender theories, and diagnostic revisions. One significant change in diagnosis involves a shift from a behavioural and sexual focus to a broader consideration of a person’s identity. This shift reflects the recognition that being transgender is not a mental disorder, with significant implications: reparative therapies, forced hospitalization, and sterilization, once aimed at altering or suppressing an individual’s gender identity, are now acknowledged as harmful and are no longer endorsed by the WHO.

Transitioning to ethical considerations, we acknowledge the unique challenges associated with researching gender dysphoria—a subject deeply entwined with personal identity, social stigma, and mental health. Our ethical approach to researching gender dysphoria is grounded in a commitment to do no harm, advance knowledge with compassion and respect, and contribute to a more inclusive and supportive society for all individuals, irrespective of their gender identity.

From: A narrative review of gender dysphoria in childhood and adolescence: definition, epidemiology, and clinical recognition. Clemente, Jasser and Koenig. [2024] Pediatric Medicine.

There is increasing evidence on the contributions of genetics, hormone influences and neurobiology on gender identity. Furthermore, data on the benefits of access to gender affirming therapy continue to emerge. Transgender youth are at increased risk of psychiatric comorbidities such as depression, anxiety, and life-threatening behaviors. As such, studies underscore the importance of early recognition, mental health support and medical intervention through hormone treatments for pubertal suppression and/or gender-affirming hormone therapy in decreasing mental health burdens and improving quality of life among the transgender youth.

Concepts of gender variance have evolved over the years and continue to do so. In the past 10 years alone, the number of transgender/gender-diverse children and adolescents has increased. Current data indicates approximately 0.1–0.2% of the general population consider themselves as transgender/gender non-conforming. Increased public awareness brought about by heightened media representation, de-stigmatization and increased understanding of gender and gender diversity, are among the proposed explanations for this upsurge in numbers. More youth considered as transgender and gender diverse, particularly those that experience gender dysphoria, seek transition-related medical care, thus there is a growing and continued need to improve knowledge and expertise in this topic.

What determines a person’s gender identity is likely influenced by multiple constructs, including biology, social interactions within one’s environment, as well as cultural dictates. Results of research focusing on biological determinants of gender development support the hypotheses of genetic, endocrine, and neuroanatomic influences on gender. Gender dysphoria was significantly associated with the number of alleles and genotypes that were studied. Another study by Fernández et al., assessed the role of oestrogen receptors alpha (ERα), beta (ERβ), androgen receptor (AR), and aromatase (CYP19A1) on brain differentiation of humans. They showed that specific genotype and allele combinations of these receptors are involved in the genetic basis of gender-diversity, and that ERβ plays an important role in brain differentiation of humans.

Previous studies that has looked into 2D:4D finger ratio in transgender individuals have contradictory results, however, in 2020, Siegmann et al. presented new data and results of a meta-analysis that showed higher (feminized) 2D:4D finger ratio in male to female transgender individuals when compared to the male controls

Similar to results of investigations on effect of genetics and hormone exposure, studies in neuroanatomy and functional neuroimaging in transgender individuals have been inconclusive; however, a main hypothesis for GD assumes that an individual’s perceived gender can be related to sexual differentiation of the brain and suggests that in transgender individuals, a deviation between sex differentiation of the brain and reproductive organs can occur, as a result of genetic factors and/or effects of testosterone during fetal development.

Children and adolescents with gender identity concerns and/or their families may also delay seeking advice or medical care which can be due to fear of stigma associated with being transgender or gender diverse, or due to lack to health care access. Primary care providers should be aware that children and adolescents who have gender dysphoria might be concerned about expressing their thoughts about their identity to their families and peers. This might be due to fear of social stigmatization from being labelled as a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ). LGBTQ adults report that experiences of interpersonal discrimination and violence that can range from emotional, verbal and physical forms. The same is true for transgender youth, who also commonly report negative experience that directed toward expressing their gender identity in term of accessing appropriate bathroom facilities or participating in gender specific activities, and other forms of school victimization.

It is considered unethical for health care providers managing individuals with gender dysphoria to deliver care that aims to make them congruent with their sex assigned at birth. The process of gender transition refer to the act of altering one’s physical, social, and/or legal characteristics to match their affirmed gender identity. For pre-pubertal children, this transition is primarily a social process, adopting gender-affirming names, hairstyles, clothing, pronouns and use of restrooms or other facilities. During this social transition, continued assessment of the person’s feelings and response to the social transformation would allow both the individual and gender care provider to have a better understanding on how to proceed.

Hormonal therapy can be provided by an endocrinologist to either halt the progression, change, assist in acquiring with secondary physical characteristic of desired gender or both. The role of gender-affirmation surgery (GAS) usually comes after hormonal therapy. GAS is a group of surgical procedure that aims to affirm an individual’s body with their gender identity. These include subcutaneous mastectomy, breast augmentation, vaginoplasty, metoidioplasty, phalloplasty and facial feminization/masculinization surgery. Most of these surgeries are performed after the age of 18 except for “masculinizing” mastectomy, which can be done at the of 16. GAS have shown multiple benefits to the patients, including an improvement of quality of life, satisfaction with appearance and body image, and decrease in gender dysphoria. Being a major surgery, the decision of GAS must be shared between the surgeon and the patient, and must be based on deep awareness of the patient own goals, expectations, associated risks and complications, and after exploration of all the alternative therapy options.

From: The Misuse of Gender Dysphoria: Toward Greater Conceptual Clarity in Transgender Health. Ashley F. [2021] Perspectives on Psychological Science

The notion of gender dysphoria is central to transgender health care but is inconsistently used in the clinical literature. Clinicians who work in transgender health must understand the difference between the diagnosis of Gender Dysphoria as defined and described in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and the notion of this term as used to assess eligibility for transition-related interventions such as hormone-replacement therapy and surgery. Unnecessary diagnoses due to the belief that a diagnosis is clinically required to access transition related care can contribute to stigma and discrimination toward trans individuals.

Gender dysphoria, which refers to the distress and dis comfort some trans people experience because of the discrepancy between their gender assigned at birth and gendered self-image, has been a centerpiece concept of trans health care in recent years. Yet wielding the unwieldy notion of gender dysphoria is an arduous task for even the most hardened of clinicians.

Noncorrespondence of gender identity and gender assigned at birth is increasingly understood as a matter of human diversity rather than as pathology. People naturally develop gender identities, and some people turn out to be trans as a result. The growing understanding of transgender identities as nonpatho logical builds on trans communities’ self-conception as normal people and is foundational in trans advocacy and scholarship. Many trans people are healthy and well-adjusted people. Applying the label of mental ill ness seems ill-suited. And although many trans people do suffer from mental-health issues, these tend to occur as a by-product of stigma and minority stress rather than because of transness.

From a depathologizing perspective, the distress in gender dysphoria is not indicative of mental illness but is a normal psychological response to having a body that does not correspond to one’s gendered self-image. Trans people’s gender identities are part of normal human diversity and, for some people, those gender identities involve gendered self-images that differ from their bodies. Because being trans is normal, resulting distress is understood as relating to the body rather than to the mind. Medical transition lessens or extinguishes gender dysphoria.

A few reasons may be given in support of giving a mental-health diagnosis. First, it may be argued that a diagnosis of gender dysphoria is helpful in guiding treatment. Second, it may be argued that the diagnosis is helpful in shielding surgeons from liability. Third, it may be argued that a diagnosis of gender dysphoria helps to identify trans patients in medical charts in hospital settings. However, trans patients have diverse medical needs, and not all trans patients are diagnosed or diagnosable with gender dysphoria.

A diagnosis of gender dysphoria is not required to access transition-related interventions in the WPATH Standards of Care. Unnecessary diagnoses of gender dysphoria are incompatible with the depathologizing animus of con temporary trans health.

From: How Early in Life do Transgender Adults Begin to Experience Gender Dysphoria? Why This Matters for Patients, Providers, and for Our Healthcare System. Zaliznyak M. et al. [2021] National Library of Medicine

The age at which transgender women (TW) and men (TM) first experience gender dysphoria (GD) has not been reported in a U.S. population of adults seeking genital gender-affirming surgery (gGAS). Because gender is an innate part of identity, we hypothesized that untreated GD would be a part of individuals’ earliest memories. Understanding GD onset can help guide providers with when and how to focus care to patients not yet identified as “transgender“.

Patients self-reported their earliest recollections of experiencing GD, earliest memories in general, and history of anxiety, depression, and suicide attempt. Our findings suggest that GD typically manifests in early childhood and persists untreated for many years before individuals commence gender transition. Diagnosis and early management during childhood and adolescence can improve quality of life and survival.

This study highlights how transgender adults tend to live many years with untreated GD before starting any form of gender-affirming transition (social, hormonal, or surgical). When we consider that life-years of any untreated condition are a robust predictor for morbidity and decreased quality of life, the number of life-years associated with GD and its associated morbidities is striking and serves as a compelling reason for intervention.

From: Gender Dysphoria: Overview and Psychological Interventions. Lavorato E, Rampino A, Giorgelli V. [2022] Practical Clinical Andrology in Springer nature.

In the DSM V, the condition known as “Gender Identity Disorder” becomes “Gender Dysphoria” in order to avoid the stigma of being labeled as carriers of psychopathology. Gender Dysphoria (GD) refers to mental discomfort deriving by incongruence between the expressed gender and the assigned one. The term Transgender refers to identities or gender expressions that differ from social expectations typically based on the birth assigned sex. Not all people living “Gender Variance” express psychological or physic discomfort. The personal gender identity develops influenced by emotionally significant relationships and by socialeducational environment, based on predisposing biological characteristics. Most of clinical and psycho-social studies agree on multifactorial nature of this process, focusing on the combined action of biological, psychological, social and cultural factors. The first symptoms of gender dysphoria may appear from first years of life and then they may persist in puberty and adulthood. The causes of Gender Dysphoria are still unclear.

Both psychosocial and biological factors have been called into question to explain the onset. The Gender Dysphoria Treatment aims to reduce, or to remove, suffering of person with GD and it is based on teamwork of psychologists, psychiatrists, endocrinologists and surgeons. The cure is, firstly, psychological and is provided by mental health experts. Hormone therapy can be prescribed to all people with persistent and well documented Gender Dysphoria if there are no medical contraindications; lastly, sex reassignment surgery. The formation and definition of transgender and transsexual identity obviously represents a specific complexity, to which is added an environmental, cultural and consequently individual and conditioning stigmatization.

Literature reports that Gender Dysphoria (GD)—defined as marked incongruence between one’s expressed gender and her/his assigned gender—is associated with psychological suffering characterized by anxiety, depression, impaired relationships, and suicidal ideation. The difference between one’s expressed gender and her/his physical sexual characteristics is expressed by the desire to get rid of them and/or to have the primary and secondary sexual characteristics of the opposite gender. The peculiarity of this disorder is the coexistence of medical aspects (biological sex) and psychological aspects (subjective experience). Previous studies highlight that psychological risk does not derive from the gender inconsistency, but from childhood traumatic experiences in different contexts, such as family, school, and because of non-recognition of psychological and sexual identity.

Therefore, Gender Dysphoria (GD) represents the condition of partial or complete discordance between assigned sex, based on external genitalia, and the gender recognized by the brain. So, it is characterized by suffering, malaise, and stress.

The term Transgender refers to identities or gender expressions that differ from social expectations typically based on the birth assigned sex. Transgender people can have a binary gender identity (identifying themselves as women if at birth they were men or as men if at birth they were women) or non-binary (identifying themselves with subjective combination of genres). Not all people living “Gender Variance” express psychological or physical discomfort. Most of them find balance between the perception of oneself and the subjective model of relationships. On the other hand, if there is a psychological or physical distress, the so-called Gender Dysphoria, the person could feel the need to adapt the external reality (anatomical and personal data) to his or her emotional inner world.

The biological sex is the set of all biological characteristics of being female or male (biological sex): the sex chromosomes (XY for males and XX for females), the gonads (testes for males and ovaries for females), external genitalia, and secondary sexual characteristics (development of breasts, presence of face hair, tone of the voice, etc.) which appear during the sexual development (puberty).

Gender is a more complex construct and refers to characteristics depending on cultural, social, and psychological factors that define typical behaviours for men and women. For most people, biological sex and gender identity match. The term transgender identifies people with gender identity other than biological sex: for example, a person born as male, but feeling female (or vice versa). The condition that gender identity differs from biological sex is known as gender incongruence. The gender incongruence is not a disorder. In the last edition of International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (ICD-11), gender incongruence was declassified from the chapter of mental health and included in the chapter of sexual health. If psychological discomfort of gender incongruence is structured in persistent and specific symptoms with an associated alteration of the global functioning, that is Gender Dysphoria.

Gender Dysphoria appears as malaise and discomfort towards one’s body, felt as a stranger; the same sense of strangeness is experienced towards behaviours and attitudes that are typical of one’s sex, within which the person does not recognize her/himself. The first symptoms of gender dysphoria may appear from the very early years of life, 2–3 years.

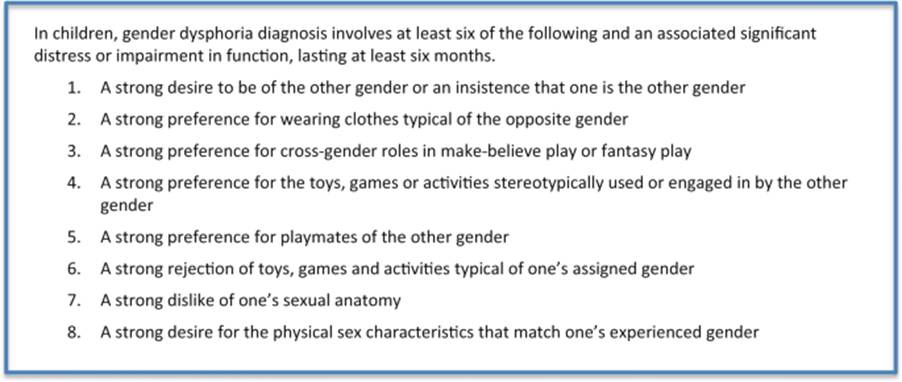

Gender Dysphoria Criteria in Children

- A marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and their assigned gender, lasting at least 6 months, as manifested by at least two of the following (one of which must be the first criterion):

- A strong desire to be of the other gender or an insistence that one is the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender).

- In boys (assigned gender), a strong preference for cross-dressing or simulating female attire; or in girls (assigned gender), a strong preference for wearing only typical masculine clothing and a strong resistance to the wearing of typical feminine clothing.

- A strong preference for cross-gender roles in make-believe play or fantasy play.

- A strong preference for the toys, games, or activities stereotypically used or engaged in by the other gender.

- A strong preference for playmates of the other gender.

- In boys (assigned gender), a strong rejection of typically masculine toys, games, and activities and a strong avoidance of rough-and-tumble play; or in girls (assigned gender), a strong rejection of typically feminine toys, games, and activities.

- A strong dislike of one’s sexual anatomy.

- A strong desire for the physical sex characteristics that match one’s experienced gender.

- The condition must be associated with clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. These behaviours in gender dysphoria are associated with deep suffering and distress at school and in relationships. Rather consistently, in children with gender dysphoria, anxiety and depression are common.

Gender Dysphoria Criteria in Adolescents

- A marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and their assigned gender, lasting at least 6 months, as manifested by at least two of the following:

- A marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and primary and/or secondary sex characteristics (or in young adolescents, the anticipated secondary sex characteristics).

- A strong desire to get rid of one’s primary and/or secondary sex characteristics because of a marked incongruence with one’s experienced/expressed gender (or in young adolescents, a desire to prevent the development of the anticipated secondary sex characteristics).

- A strong desire for the primary and/or secondary sex characteristics of the other gender.

- A strong desire to be of the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender).

- A strong desire to be treated as the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender).

- A strong conviction that one has the typical feelings and reactions of the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender).

- The condition must also be associated with clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. It is very difficult to have or suppress these feelings, and as a result, people with gender dysphoria may present with anxiety, depression, engage in self-harm, and have suicidal thoughts.

In both children and adults investigate as to whether a Sexual Development Disorder is present.

The causes of Gender Dysphoria are still unclear and both psychosocial and biological factors have been implicated. Currently, the most accepted hypothesis is that both factors contribute to its development [6, 7]. Even if social factors, such as education, environment, and events of life, are of great importance in emergence of gender dysphoria, there is still no experimental evidence to support this theory.

Other studies focused on brain area differences between male and female population and suggested that cerebral architecture of individuals with Gender Dysphoria resembles the one of individuals with the same gender identity rather than those with the same biological sex, thus suggesting that non-biological factors may play a predominant role in GD genesis.

Treatment of Gender Dysphoria aims to reduce, or remove, suffering based on teamwork of psychologists, psychiatrists, endocrinologists, and surgeons. Treatments are not always necessary and the treatment process is not the same for all people. Indeed, the procedure is different according to real needs of the individual.

First line treatment of GD in children and adolescents is psychological intervention that must be provided by mental health experts (child psychologists and neuropsychiatrists), especially if specialized in issues related to developmental age. Psychological support allows to face current problems and provides help to reduce emotional suffering sometimes allowing for more drastic treatment avoidance.

The approach to Gender Dysphoria in adolescence requires careful evaluation, with particular care in making differential diagnoses with other conditions in order to define individualized paths. For example, it is important to distinguish Gender Dysphoria from internalized homophobia that occurs in some adolescents who, failing to accept their homosexual orientation, may require a medical gender reassignment (GR). Depending on the cultural context, their belief system, or even stereotyped views of social arrangements, some homosexual adolescents may mistake their sexual orientation for gender identity, due to a history of borderline behaviours and cross-gender interests in childhood.

The treatment for adults should consist of; psychological support if necessary, feminizing or masculinizing hormone treatment (cross-sex therapy), Sex reassignment surgery.

A significant part of transgender people’s suffering originates precisely from the stigmatization deriving from a stereotyped vision of the concept of gender along with all additional stressors, connected to the stigma of gender non-conformity, and that may negatively affect the psycho-physical health of the individual. This phenomenon, known as Minority Stress, affects people belonging to social categories stigmatized and subjected to excessively high levels of stress, such as those derived from violence, discrimination, and stigmatization.

The formation and definition of transgender and transsexual identity have a high specific complexity, to which environmental and cultural stigmatizations add further complexity. However, it is essential to recognize that the transgender and transsexual evolutionary path preserves the typical dynamics of any identity construction process. Therefore, in clinical work with these people, it is important to consider both the identity structure of the person and the universal evolutionary processes. Approaching transsexual people with the prejudice of an absolute diversity in the formation of the self and identity can compromise the understanding of psychological processes behind while preventing from a fully empathic relationship, that is needed in order to establish a good therapeutic alliance.

Highlighted References (Under development)

Key Literature References

*** What is the Best Approach to Removing the Social Stigma from the Diagnosis of Gender Dysphoria? (2025), by Charalampos Milionis, published in Health Care Analysis

*** Perspectives about key measures of gender dysphoria based on interviews with people with lived experience of gender dysphoria (2025), by Karl Mears & Chris Ashwin published in International Journal of Transgender Health

*** Systematic review of prospective adult mental health outcomes following affirmative interventions for gender dysphoria (2025), by Lucas Shelemy, et al, published in International Journal of Transgender Health

*** An Integrated Framework for Conceptualizing and Measuring Gender Dysphoria: Development and Psychometric Evaluation of the Multidimensional Gender Dysphoria Measure (2025), by M. Paz Galupo, et al. published in American Psychologist

*** Predicting NSSI among trans young people: the role of transphobic experiences, body image, and gender dysphoria (2025), by Kirsty Hird, et al., published in International Journal of Transgender Health

*** Reevaluating gender-affirming care: biological foundations, ethical dilemmas, and the complexities of gender dysphoria (2025), by Marc J. Defant, published in Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy

(Notable) *** Mapping the Evolution of Gender Dysphoria Research: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Study (2024), by Massimo Aria, Luca D’Aniello, Maria Gabriella Grassia, Marina Marino, Rocco Mazza & Agostino Stavolo, published in the journal Quality & Quantity

*** Assessing Gender Dysphoria: Development and Validation of the Gender Preoccupation and Stability Questionnaire – 2(nd) Edition (2024), by Sarah Joy Bowman, et al., published in the Journal of Homosexuality

(Notable) *** A narrative review of gender dysphoria in childhood and adolescence: definition, epidemiology, and clinical recognition (2024), by Ethel Gonzales Clemente, et al., published in Pediatric Medicine

*** Physical and psychosocial challenges of people with gender dysphoria: a content analysis study (2024), by Zahra Ghiasi, et al., published in BMC Public Health

*** Gender-Related Minority Stress and Gender Dysphoria: Development and Initial Validation of the Gender Dysphoria Triggers Scale (GDTS) (2023), by Chloe Goldbach& Douglas Knutson, published in the journal Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity

*** Gender Dysphoria: Overview and Psychological Interventions (2023), by Elisabetta Lavorato, et. al, published in the textbook Practical Clinical Andrology (Carlo Bettocchi, et. al, editors)

*** Assessing Gender Dysphoria: A Systematic Review of Patient-reported Outcome Measures (2023), by Sarah Joy Bowman, et. al, published in the journal Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity

(Notable) *** The Misuse of Gender Dysphoria: Toward Greater Conceptual Clarity in Transgender Health (2021), by Florence Ashley, published in the journal Perspectives on Psychological Science

(Notable) *** How Early in Life do Transgender Adults Begin to Experience Gender Dysphoria? Why This Matters for Patients, Providers, and for Our Healthcare System (2021), by Michael Zaliznyak, et al., published in the journal Sexual Medicine

*** Trapped in the Wrong Body? Transgender Identity Claims, Body-Self Dualism, and the False Promise of Gender Reassignment Therapy (2021), by Melissa Moschella, published in The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy

(Notable) *** Age at First Experience of Gender Dysphoria Among Transgender Adults Seeking Gender-Affirming Surgery (2020), by Michael Zaliznyak, et al., published in JAMA Network Open

*** “Every Time I Get Gendered Male, I Feel a Pain in my Chest”: Understanding the Social Context for Gender Dysphoria (2020), by Galupo, M.P., Pulice-Farrow, L., & Lindley, L., published in the journal Stigma and Health

*** Gender Dysphoria: Definitions, Classifications, Neurobiological Profiles and Clinical Treatments (2020), by Giulio Perrotta, published in the International Journal of Sexual and Reproductive Health Care

(Notable) *** Etiological Factors and Comorbidities Associated with “Gender Dysphoria”: Definition, Clinical Contexts, Differential Diagnosis, and Clinical Treatments (2020), by Giulio Perrotta, published in the International Journal of Sexual and Reproductive Health Care

*** The Phenomenology of Gender Dysphoria in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis (2020), by Kate Cooper, et. al, published in the journal Clinical Psychology Review

*** Gender Dysphoria in Adults: An Overview and Primer for Psychiatrists (2018), by William Byne, et. al, published in the journal Transgender Health

*** Epidemiology of Gender Dysphoria and Transgender Identity (2017), by Kenneth Zucker, published in the journal Sexual Health

>> (Chapter 3) What research has focused on gender incongruence, and how is it distinct from gender dysphoria?

Overview by Ian Cameron